Executive Summary

Large language models (LLMs) are useful for general conversation, however they struggle to achieve the precision and reliability needed for specialised downstream tasks, such as document analysis and incident classification.

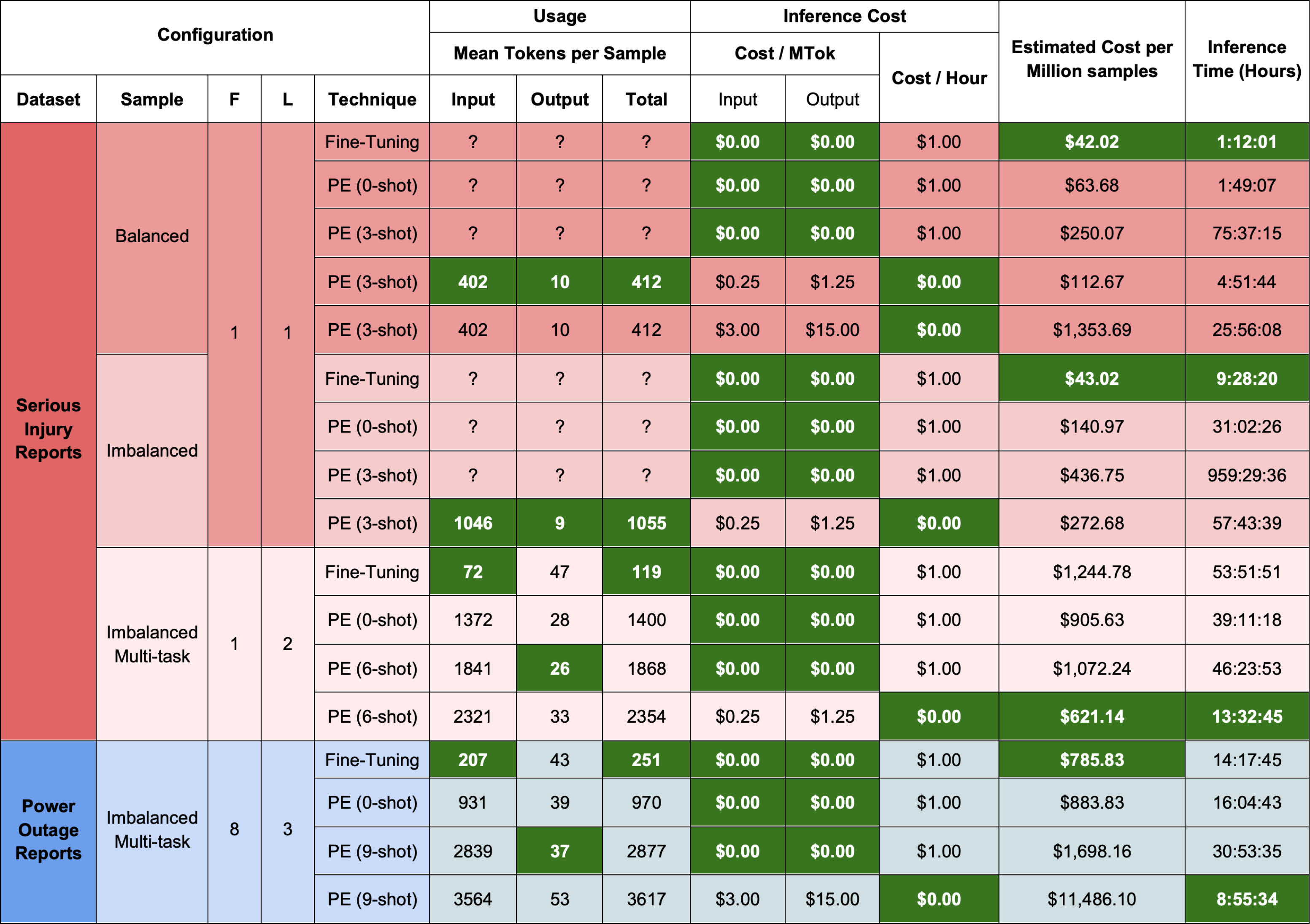

Two techniques have emerged to sharpen the knowledge of LLMs for downstream task adaptation: Prompt Engineering (PE) and Fine-Tuning (FT). We conducted an empirical comparison of these two techniques across diverse text classification tasks and model scales reflecting real-world conditions. After systematically evaluating each technique, we conclude that FT delivers far greater accuracy and cost efficiency than PE, even when FT deployed on small, locally-hosted LLMs with less than 10B parameters is compared to PE delivered on state-of-the-art cloud-based LLMs. FT requires a greater data, time, and cost investment to train than PE, but it is more affordable in the long-term owing to significantly lower inference costs and token efficiency. For business domains such as medicine, compliance, and engineering, FT is preferable for its superior accuracy and domain alignment, whilst PE is preferable for short-term deployments where training data is scarce and task definitions are fluid, such as emerging technologies and early-stage product development.

The Strategic Imperative of LLM Specialization

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4, Claude 3.5, and Llama 3 marks a pivotal moment in the landscape of artificial intelligence. These general-purpose models, with their unprecedented ability to understand, generate, and interact with human language, are fundamentally reshaping how software applications can be built and deployed across industries. For application engineers and AI/ML leaders aiming to harness this transformative power, a critical strategic decision emerges early in the development lifecycle: how best to adapt these powerful but inherently generic LLMs to the highly specific, often nuanced, requirements of enterprise-level tasks.

While general LLMs excel at broad conversational tasks and open-ended queries, their direct application to specialized domains – such as analysing legal documents, extracting financial data from public reports, or classifying incidents – often falls short of the precision and consistency required for downstream use. This gap between general capability and domain-specific excellence necessitates adapting the default behaviours of the model.

Two dominant paradigms have emerged to bridge this gap: Prompt Engineering (PE), which involves crafting sophisticated input queries and instructions to guide an existing model's behavior without altering its underlying architecture, and Fine-Tuning (FT), a process that updates the model's internal parameters using task-specific data to embed domain knowledge and behavioral patterns more deeply.

Both approaches aim to enhance task performance, yet they differ significantly in their demands for data, computational resources, development effort, and the inherent nature of the resulting model specialization. Anecdotal evidence and internet discussions often lean towards one approach over the other, creating a landscape of limited empirical guidance tailored to the real-world engineering constraints and strategic objectives faced by organizations. This article addresses this gap by providing an empirical comparison of Prompt Engineering and Fine-Tuning across diverse, real-world supervised text classification tasks. Our aim is to equip AI/ML leaders with data-driven insights to make informed decisions about LLM integration, optimizing for accuracy, efficiency, and effective domain alignment within their strategic initiatives.

Understanding LLM Adaptation Strategies

As organizations increasingly seek to operationalize LLMs for specialized tasks, understanding the trade-offs between PE and FT becomes essential for aligning limited technical resources with business objectives.

PE offers a rapid, low-barrier approach, requiring no training data or upfront time investment. Its iterative nature enables agile refinement of model behavior, and when paired with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), it allows for quick iteration of a model’s behaviour by dynamically changing the prompt to incorporate external information. However, PE is only effective with access to large, general-purpose LLMs with powerful intuition to address domain-specific queries. These models are often expensive to deploy and maintain, even at reduced scale.

In contrast, FT enables smaller, local models to rival state-of-the-art LLMs within domains where well-defined training data is accessible. Through rigorous training, FT models develop an implicit understanding of the target domain to solve complex downstream problems. FT models can capture long-range dependencies within natural language data – subtle connections between samples far apart in time or space – to classify future samples with high accuracy even when vital context is missing. FT models also strictly observe any standardized output formats or patterns from the training data without explicit instruction, which can be useful for downstream applications such as tool calling or API invocation. Finally, FT models can be affordably deployed on consumer-grade hardware, reducing reliance on cloud infrastructure. Yet, the benefits of FT are bounded by the availability of high-quality labeled datasets and a lack of generalization beyond the trained task.

For AI/ML leaders, the decision to invest in either FT and PE represents a strategic trade-off. FT offers deep domain alignment and consistent task performance, but its effectiveness is contingent on access to high-quality, labeled data and sufficient infrastructure for model retraining. PE, by contrast, enables rapid iteration and broader applicability across tasks, yet often requires access to large-scale models and incurs higher operational costs at inference time.

Comparing Adaptation for Real-World Problems

While theoretical distinctions between PE and FT offer a useful framework, they remain incomplete without empirical validation. To support strategic decision making, it is essential to quantify each approach’s accuracy in complex, real-world domains, along with the associated costs of training and inference across varying model scales. To address these questions, we outline a systematic methodology using controlled experiments to compare PE and FT on two real-world text classification datasets.

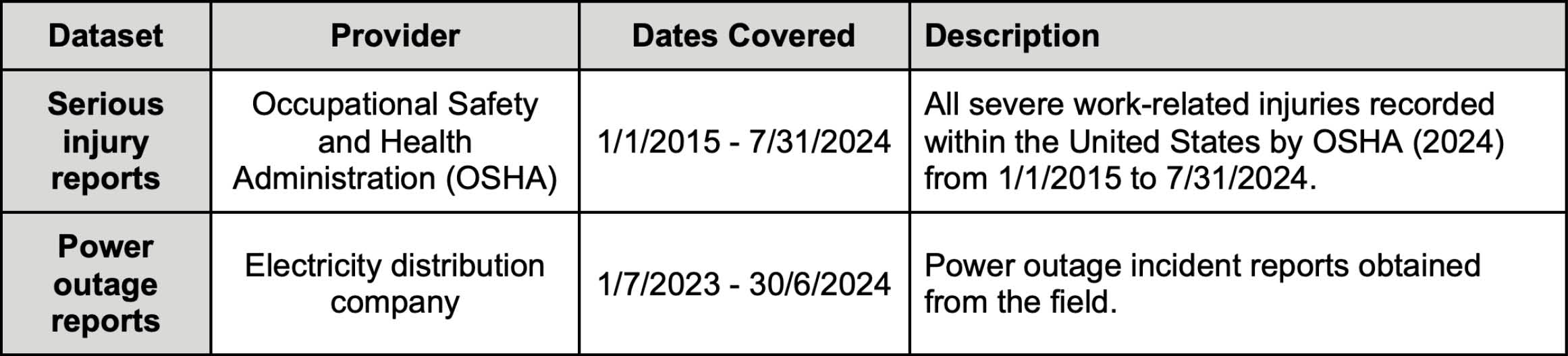

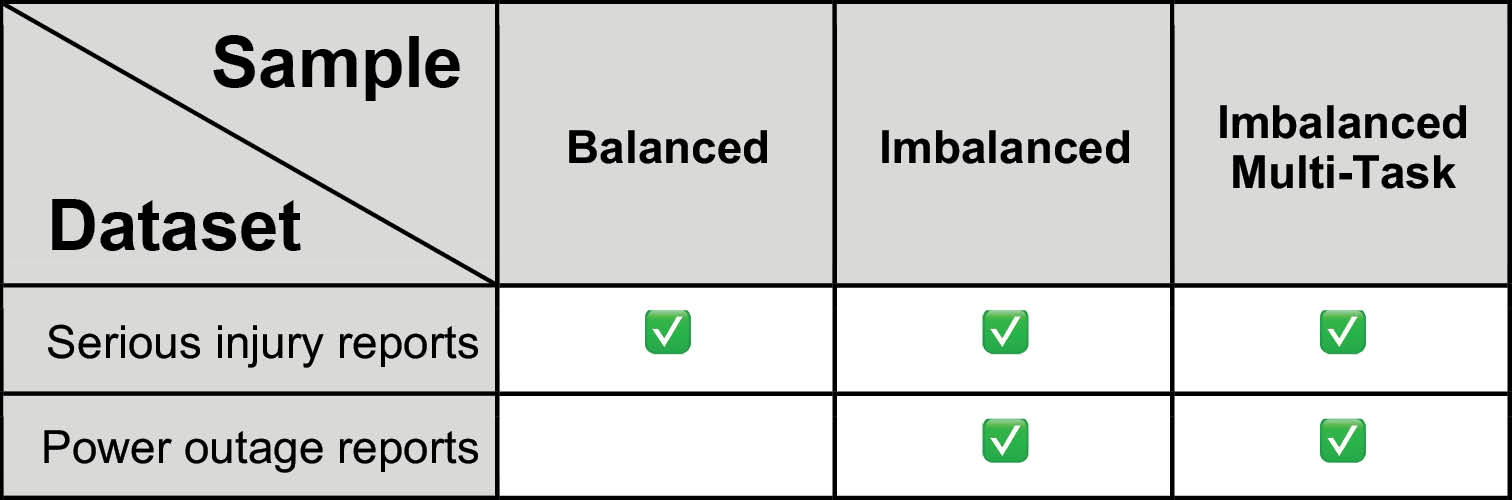

Datasets

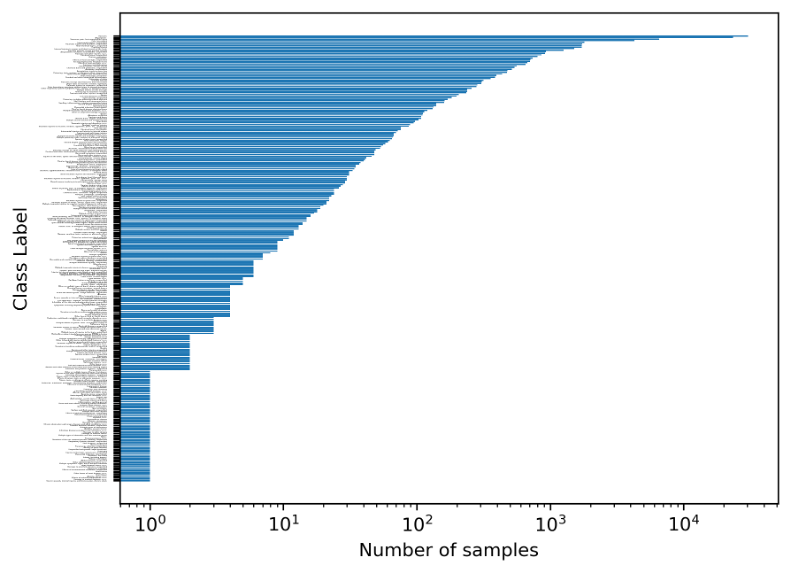

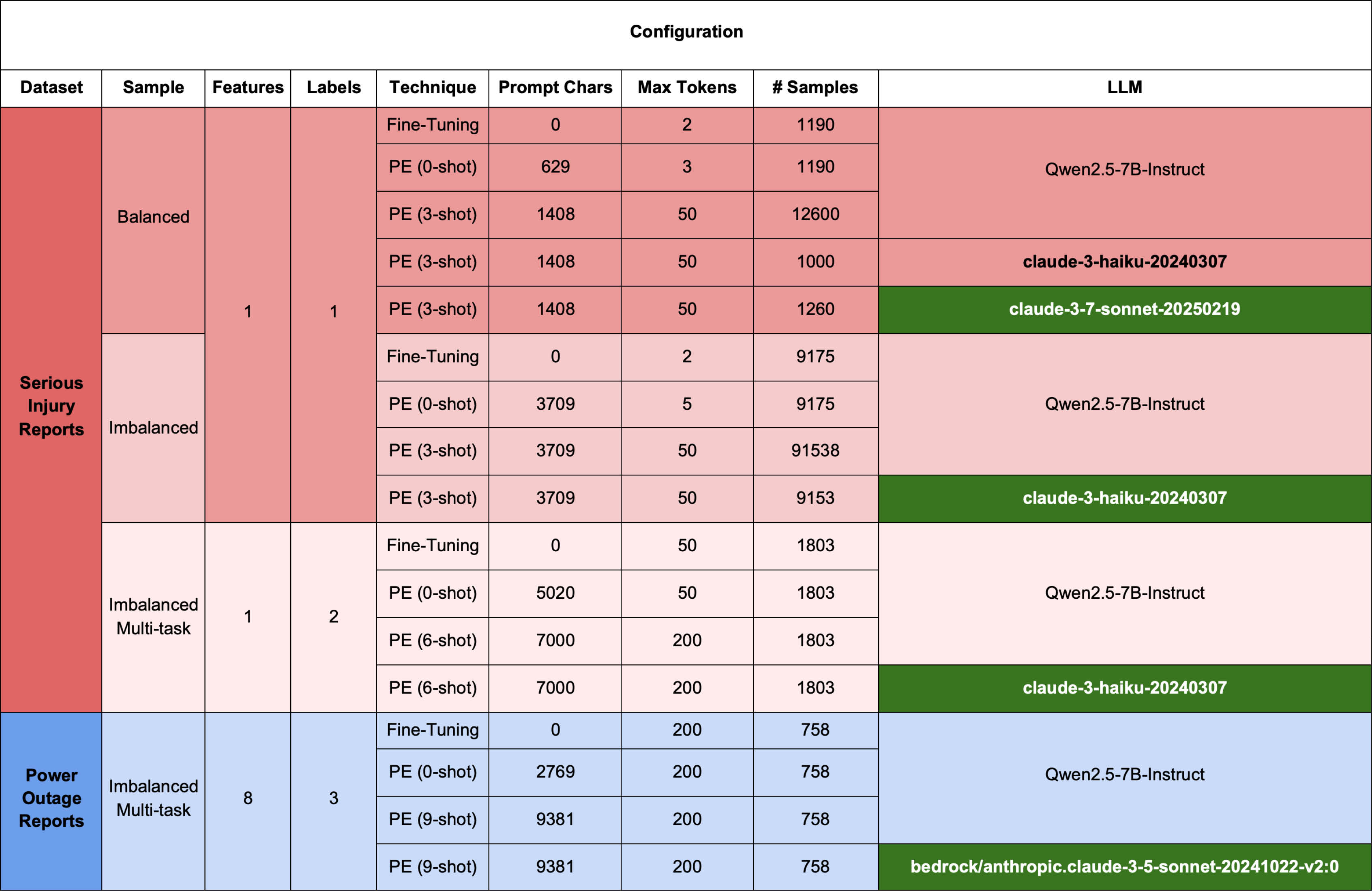

Two supervised text classification datasets were selected from enterprise domains: occupational health and safety (serious injury reports) and electrical engineering (power outage reports). These datasets reflect practical classification challenges, including class imbalance, multi-task labeling, and domain-specific language. To prepare each dataset for model training and inference, they were split into training (64%), validation (16%), and test (20%) subsets.

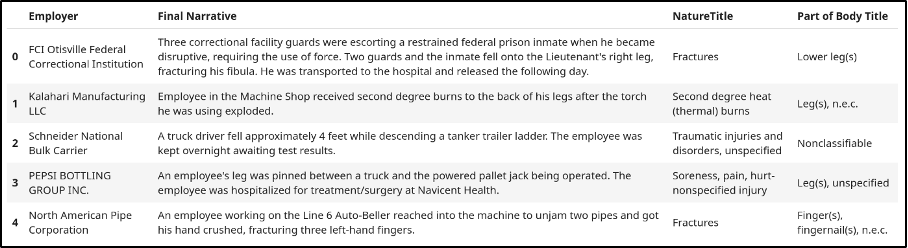

Serious Injury Reports

The serious injury reports dataset comprises 93,590 entries each detailing a workplace incident. The dataset includes three key fields relevant to classification: the Final Narrative, a natural text description of the injury event; the NatureTitle, which assigns the injury type to one of 282 predefined categories; and the Part of Body Title, which identifies the anatomical region affected. These structured labels, paired with rich narrative context, enable single- and multi-task text classification that reflects real-world complexity in occupational health and safety reporting.

Power Outage Reports

The power outage reports dataset contains 8 input text fields which describe the outage event in terms of its location, weather conditions, and fault description, and 3 output labels which identify the cause of the outage, the object damaged, and the type of damage sustained.

Classification Strategies

Two text classification strategies were employed for the serious injuries dataset:

- Single-task classification

For each sample, Final Narrative was used as input text and NatureTitle was used as the label. - Multi-task classification

For each sample, both NatureTitle and Part of Body Title were used as labels. This strategy is also known as multi-class multi-output classification because each sample is assigned a label for several independent classes.

For the power outages dataset, only multi-task classification was employed.

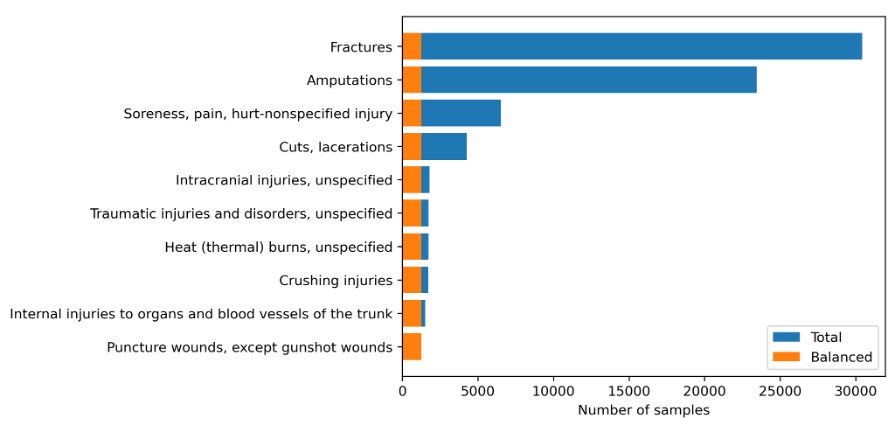

Dataset Sampling

To evaluate model performance under varying class distributions, three sampling strategies were employed:

- Balanced (Single-task):

For single-task classification, an equal number of samples were extracted from the ten mostfrequently occurring classes, creating a uniform class distribution suitable for baseline comparison.

- Imbalanced (Single-task):

All classes containing at least 50 examples were included without rebalancing, preserving the natural skew of the dataset to reflect real-world classification challenges.

- Imbalanced (Multi-task)

For multi-task classification, only imbalanced samples were used because it was impossible to extract an equal number of samples for all labels for all classes. It is possible to approximate an equal class distribution for multi-class data, but this is an optimization problem outside of the scope of this project.

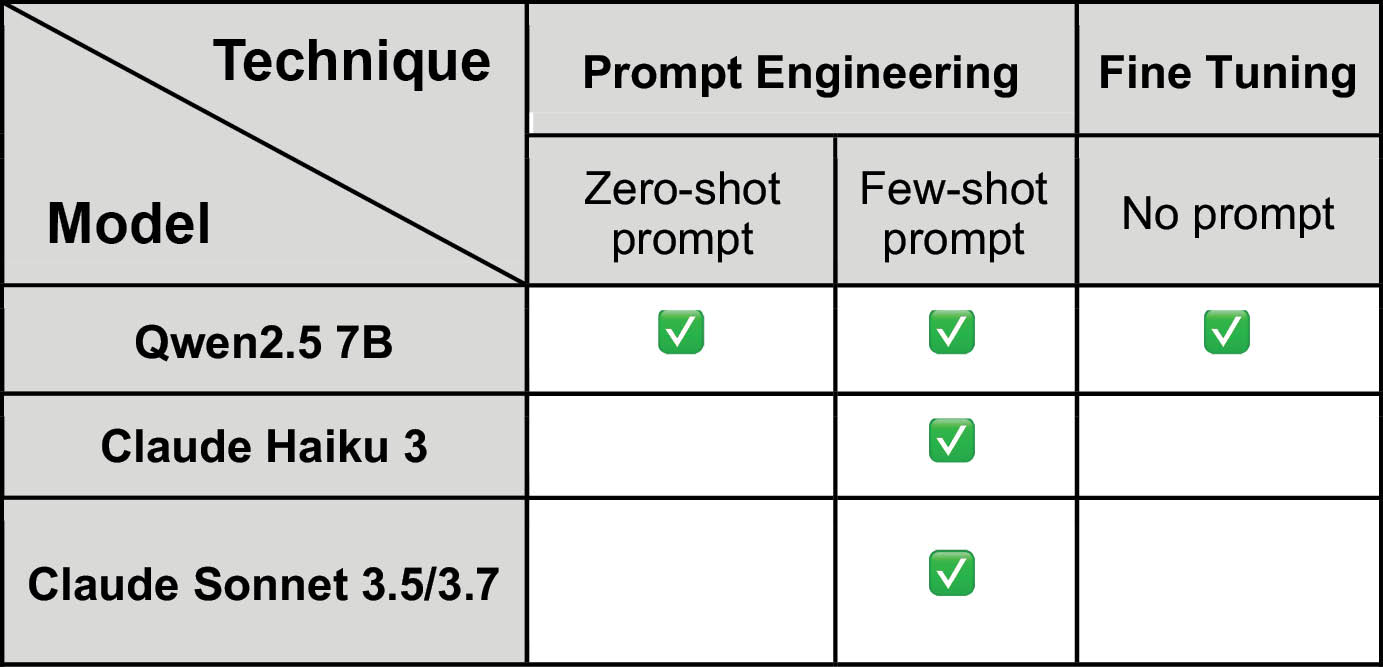

Models

Two categories of LLMs were evaluated: small, locally deployable models (Qwen 2.5 7B) and large, cloud hosted models (Claude Haiku 3, Claude Sonnet 3.5/3.7). This selection enabled comparison across deployment scales, from consumer-grade hardware to enterprise-grade cloud infrastructure.

Adaptation Techniques

All models were evaluated on identical datasets using consistent metrics to ensure comparability. Small LLMs were tested for both PE and FT classification performance, whilst large LLMs were only tested for PE.

Evaluation Process

To conduct FT and PE on the supervised text classification datasets using both locally-hosted and cloud-based LLMs of varying scales, a systematic experimental pipeline was established.

Prompt Engineering

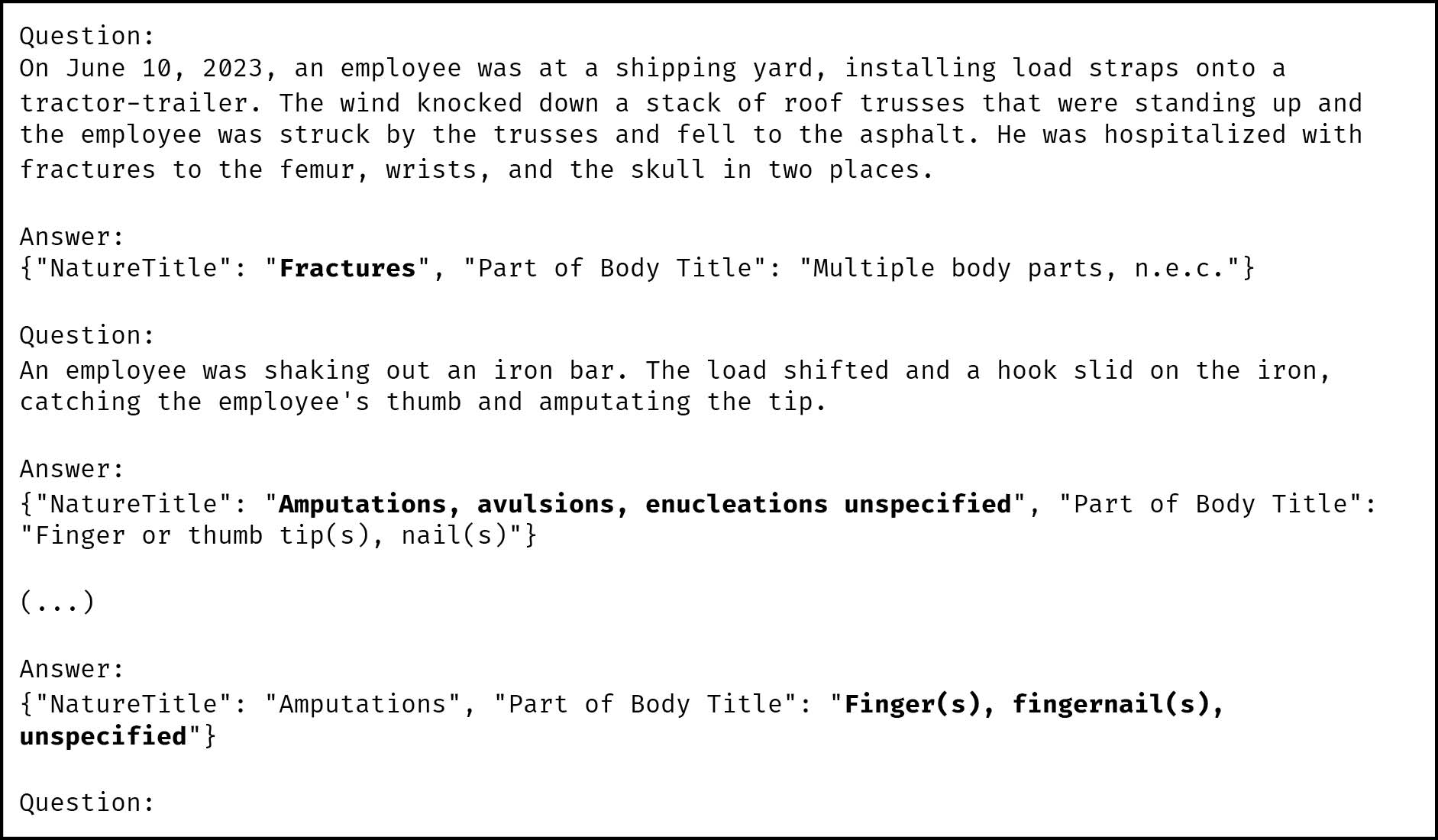

Zero-shot Prompts

To establish a baseline, each dataset(serious injury reports and power outage reports) was evaluated in a zero-shot configuration using a small language model (Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct).Each input sample was framed as a user query with a generic instruction template and no examples using the following classification prompt structure:

For multi-task classification – where the LLM must output multiple independent class labels for each sample – the LLM must provide a JSON response containing each class label. We achieved this using the following prompt inspired from Zhao et al. (2024).

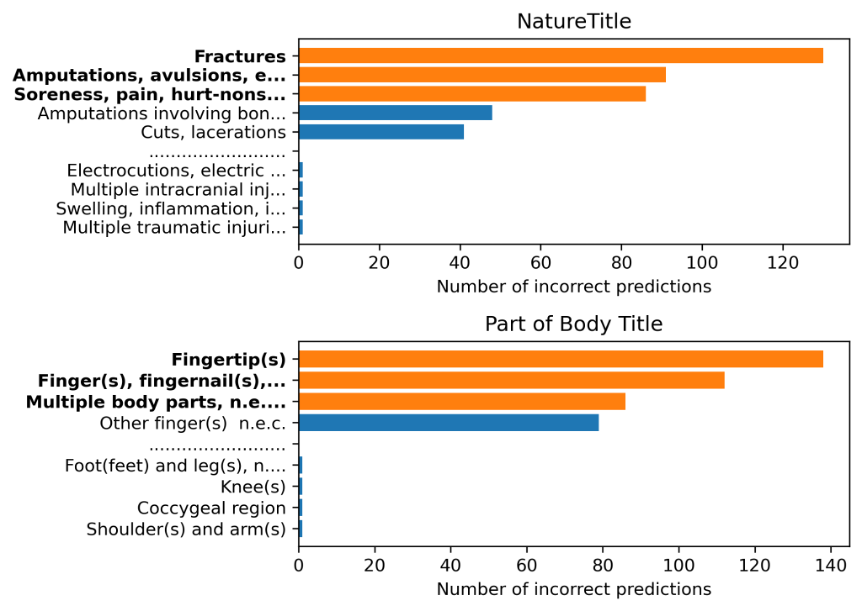

Few-shot Prompts

After running zero-shot classifications for each dataset and sampling configuration, we were able to generate targeted few-shot examples to improve classification performance. For each zero-shot classification pass, we identified the three most incorrectly predicted labels for each class. For example, these were the most inaccurately predicted classes for the serious injuries dataset using imbalanced multi-task sampling:

For each poorly predicted label, we generated a targeted few-shot example to improve LLM classification performance. These are the few-shot examples for the serious injuries dataset:

Fine-Tuning

Data Preparation

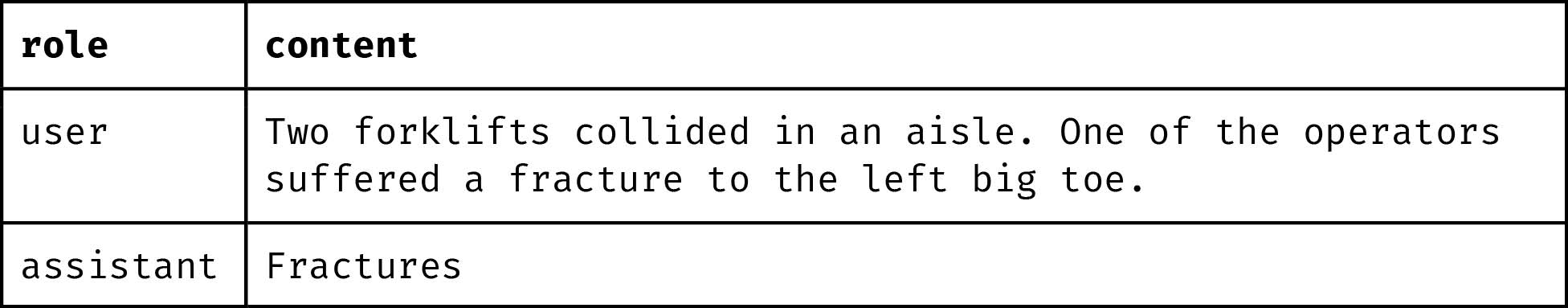

To fine-tune a local language model on the serious injury and power outage report datasets, each dataset was reformatted into a conversational structure to align with instruction-tuned LLM input expectations. In this format, each data sample simulates a user–LLM interaction where the input text is framed as a user query and the target label is treated as the model’s response. For the single-task classification of serious injury reports, the description of each injury (Final Narrative) is presented as the user prompt, whilst the corresponding category of the injury (NatureTitle) is used as the expected model output.

In Python, this structure is implemented using a list of dictionaries.

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Two forklifts collided in an aisle. One of the operators suffered a fracture to the left big toe."},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "Fractures."}

]

For multi-task classification, the model is trained to predict both the injury category (NatureTitle) and the affected body part (Part of Body Title) from the same incident description. These two labels are encoded into a single LLM response using a JSON data structure, enabling the model to learn joint prediction behavior while maintaining compatibility with downstream systems that consume structured outputs.

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Two forklifts collided in an aisle. One of the operators suffered a fracture to the left big toe."},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "{\"NatureTitle\" : \"Fractures\", \"Part of Body Title\" : \"Toes(s), toenail(s)\"}"}

]

It’s important to note that the LLM’s output remains a string: no changes are made to the underlying response data type. Instead, we embed structured information within the string to enable post-processing and label extraction, effectively multiplexing the output. This same technique can be extended to support multiple input features per sample. For example, incident descriptions can be paired with metadata such as company name to improve predictive accuracy for injury classification. While it may seem that increasing the number of input features and output labels could compromise the model’s ability to consistently generate well-formed JSON, our experiments show otherwise. Even small, open-source models like Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct (7 billion parameters) reliably produce structured JSON outputs when tasked with predicting up to three distinct labels from eight input features, all encoded within a single prompt. This demonstrates the viability of structured multi-label classification using compact LLMs in real-world deployment scenarios.

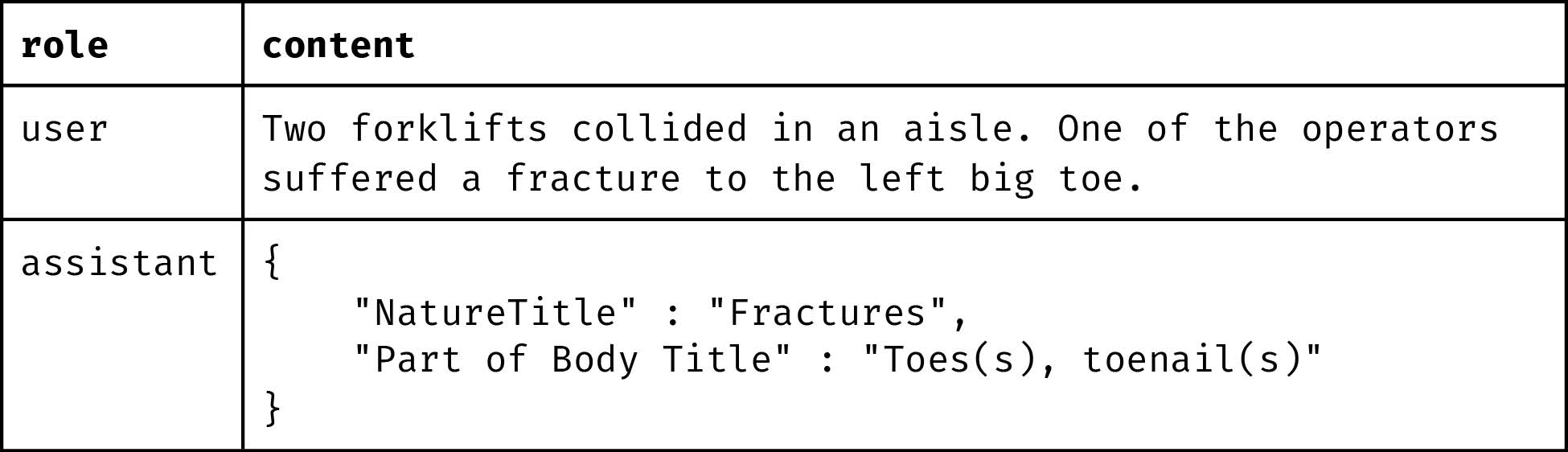

Training Procedure

To fine-tune a small language model (Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct) for supervised text classification tasks, we employed Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation (QLoRA): a parameter-efficient Fine-Tuning technique optimized for consumer-grade GPUs. QLoRA begins by quantizing the base model, significantly reducing its VRAM footprint. It then injects a lightweight set of trainable parameters, known as adapters, into the model architecture. During Fine-Tuning, QLoRA only updates the adapters while the base model’s weights remain frozen. This approach minimizes computational overhead, preserves the model’s pre-trained knowledge, and mitigates the risk of catastrophic forgetting. By combining Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning with quantization, QLoRA enables high-performance Fine-Tuning of LLMs on consumer-grade GPUs, making domain adaptation feasible without enterprise-scale infrastructure.

Quantifying the Performance Divide

To quantify the performance divide between LLM adaptation strategies, we systematically evaluated the classification accuracy of LLMs using both PE and FT techniques across local and cloud-based deployments on two real-world datasets. Latency was measured as the average prediction time per sample, expressed in seconds, to reflect practical inference efficiency.

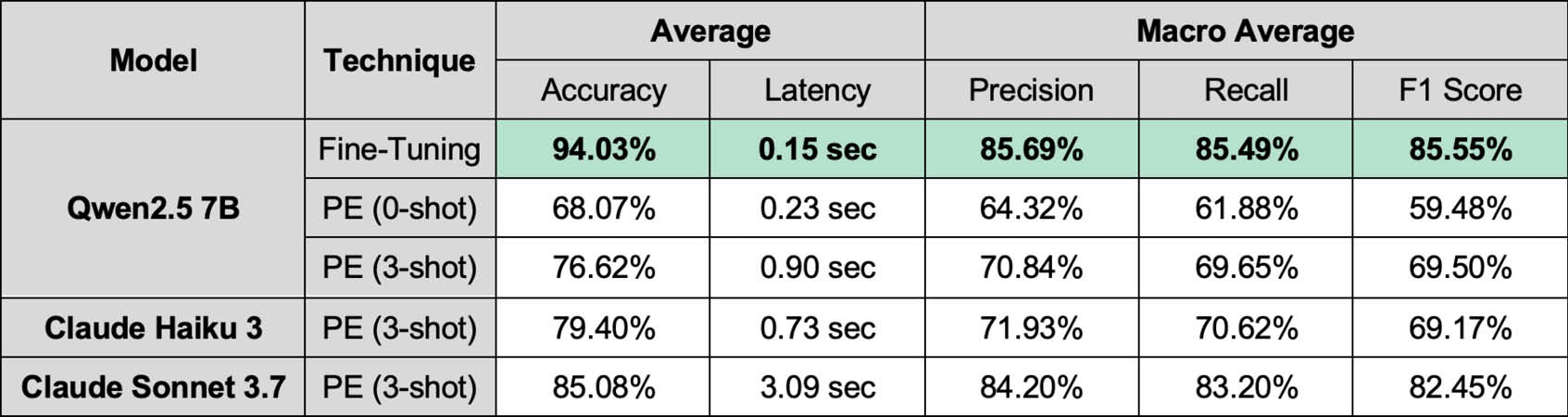

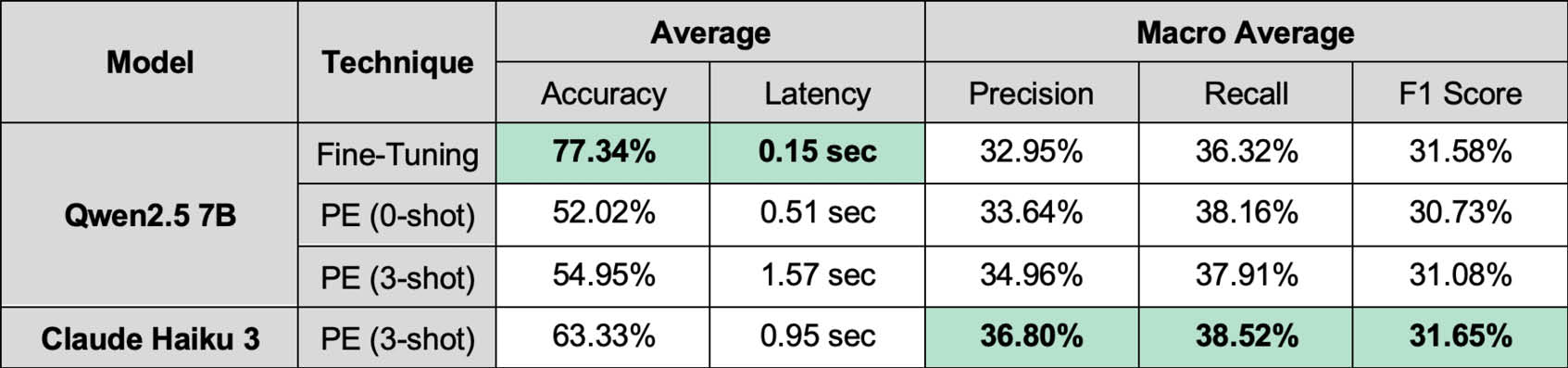

Serious Injury Reports

Balanced Dataset

Imbalanced Dataset

Imbalanced Multi-task Dataset

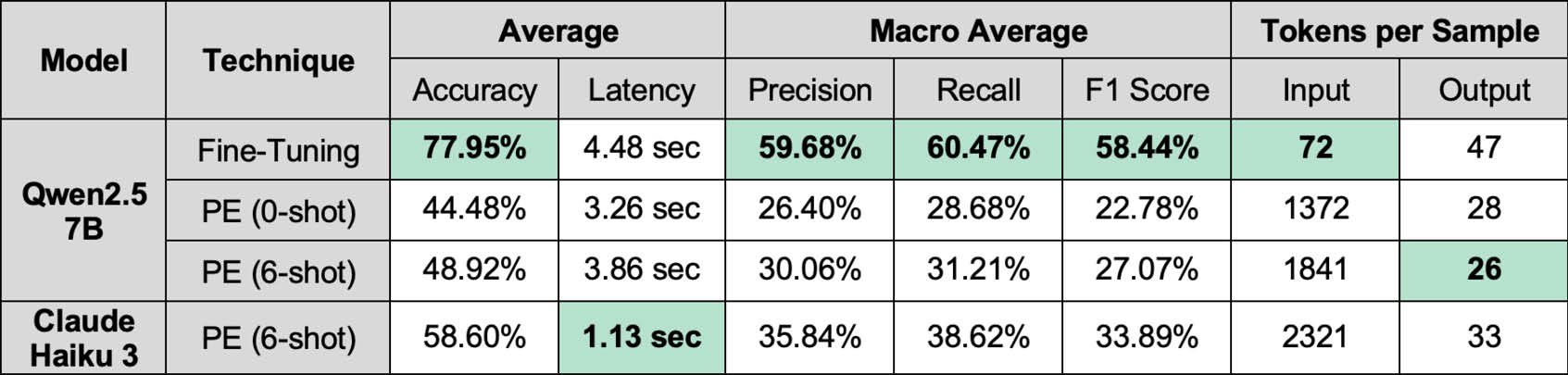

Power Outage Reports

Imbalanced Multi-task Dataset

Summary

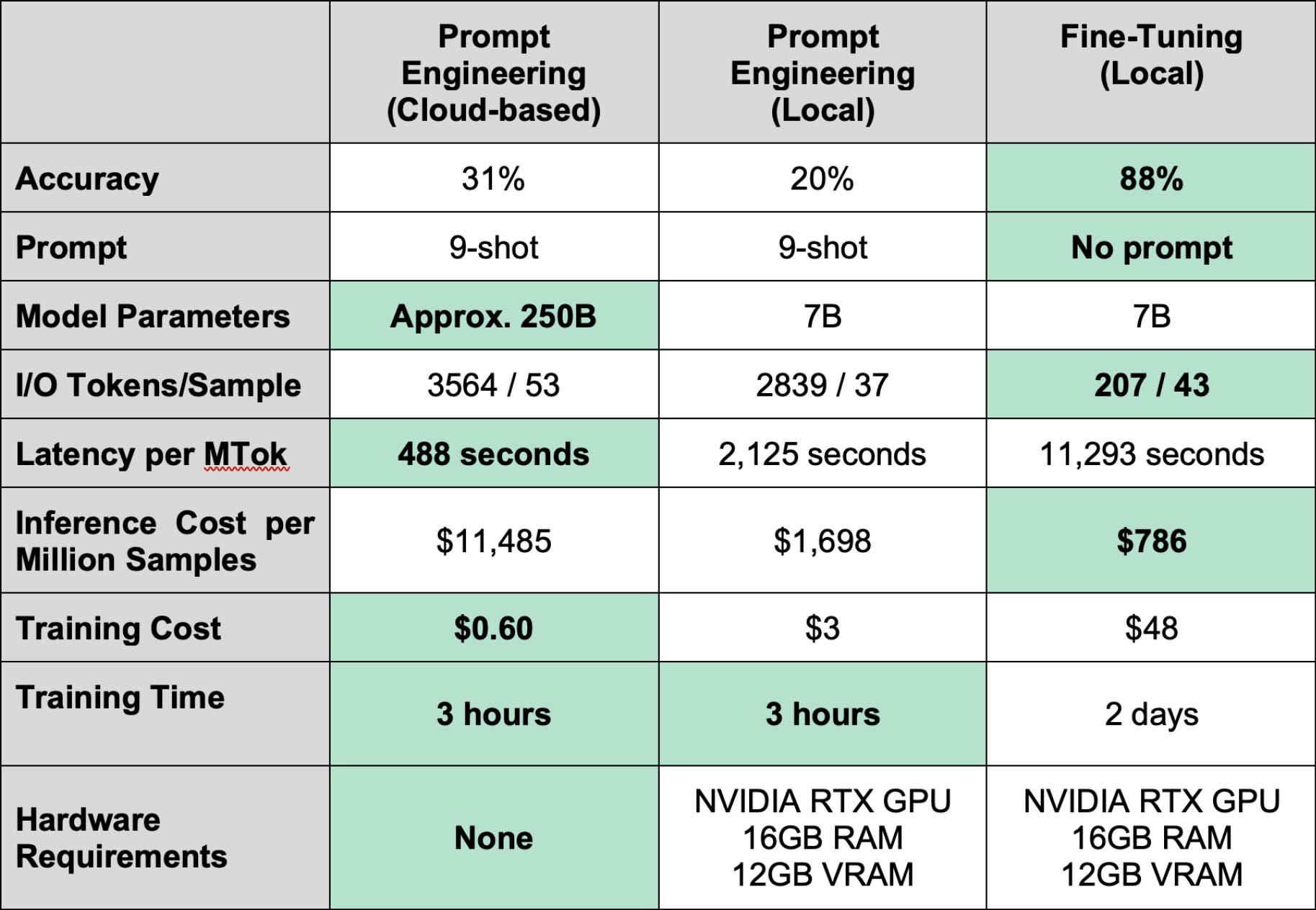

For text classification tasks, the efficacy of FT compared to PE was systematically evaluated. This table summarises our results from a real-world electrical engineering dataset

Assumptions:

- Costs are in USD.

- It costs $1 USD / hour tolocally run a Linux machine with:

- NVIDIA A10G GPU.

- 16GB of RAM.

- 22GB of VRAM.

- On-premises compute specs and costs are equivalent to AWS’ g5.xlarge model. https://aws-pricing.com/g5.xlarge.html

- It takes 2 days to fine-tune anLLM on a supervised text classification dataset.

- To develop an effective 9-shot classification prompt, it takes:

- 3 hours of Prompt Engineering.

- 35,000 input and output tokens.

- Claude Sonnet 3.5/7 has a model size of approximately 250B parameters.

Strategic Implications for AI/ML Leadership

We systematically compared the performance of two LLM adaptation strategies: Fine-Tuning (FT) and Prompt Engineering (PE) for supervised text classification tasks. Using two real-world datasets in the domains of occupational health and safety and electrical engineering, we ran experiments to capture the accuracy, affordability, and efficiency of each adaptation strategy across varying model scales and deployments. From our experiments, we find that FT is generally superior to PE for supervised text classification tasks.

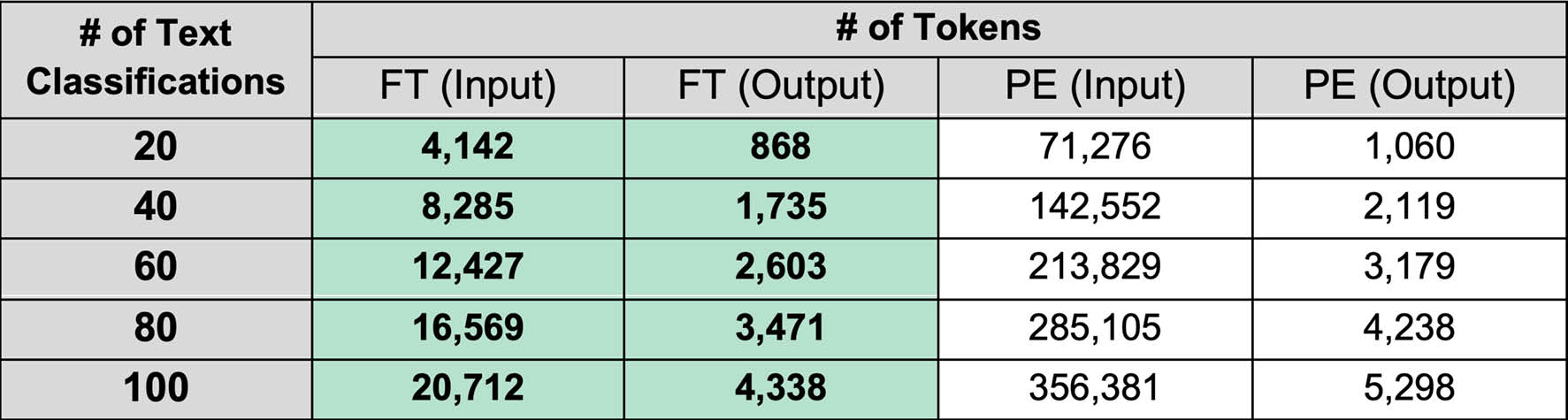

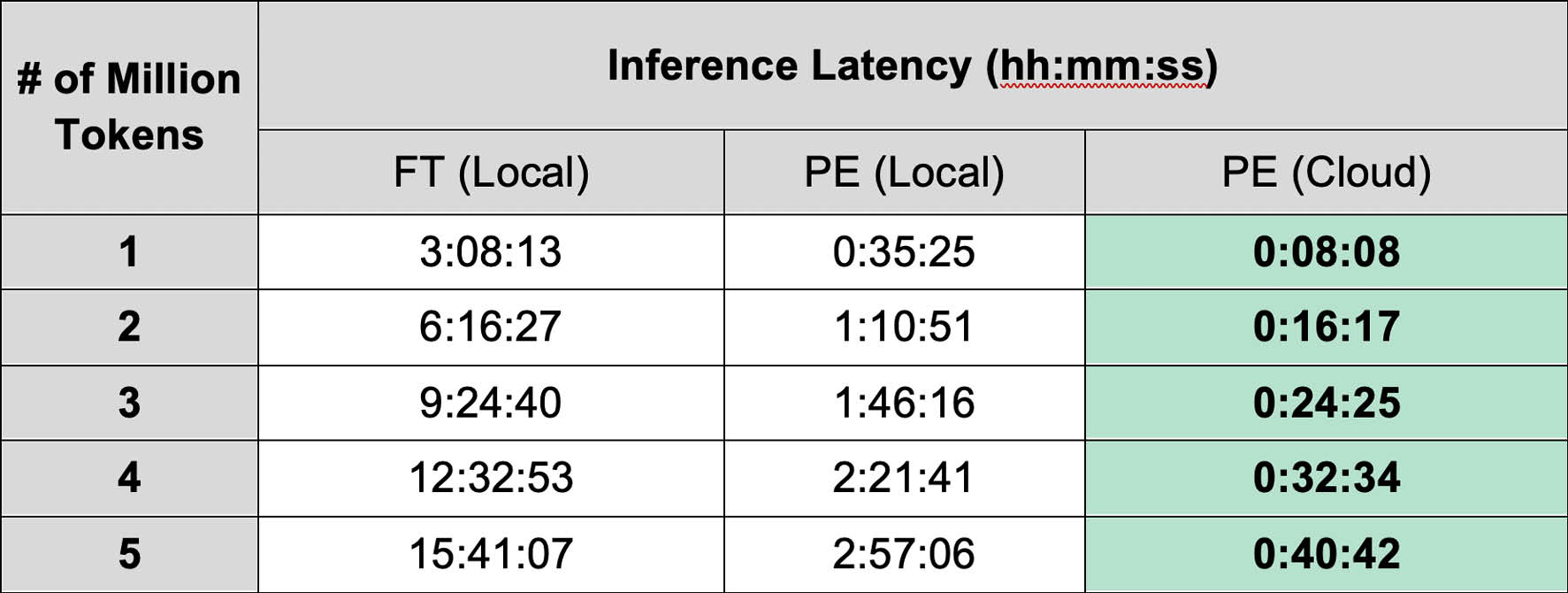

FT is more affordable than PE for non-trivial deployments. Despite incurring an initial $48 USD training cost, FT’s inference costs are exponentially cheaper than PE, costing $789 per million text classifications for FT compared to $11,485 per million for PE, making FT far more affordable for enterprise-scale deployments. FT’s low inference costs are partially explained by its token efficiency: FT models require far less input tokens per sample compared to PE. When classifying samples with PE, each sample must be appended with an exhaustive list of classification instructions and few-shot examples to be classified correctly. This restriction does not exist for FT; only the input text is needed for a successful classification.

Finally, we find that FT is far more accurate than PE in spite of its exponentially smaller model size. We systematically measured how accurately FT and PE could identify the causes of electrical power outages and serious injuries given a textual description. The FT model (Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct) was far smaller than the PE model (Claude Sonnet 3.5 / 3.7), having 7 billion parameters compared to hundreds of billions of parameters. Despite this, FT was far more accurate than PE for both datasets, achieving an accuracy of 88% for the power outage reports compared to PE’s 31% accuracy and 78% for the serious injury reports compared to PE’s 59% accuracy.

The only advantage PE has over FT for supervised text classification tasks is quicker training and inference time. PE models require little upfront time or cost investment to develop and can generate classifications faster than FT models. PT may be viable within environments defined by rapid change, evolving requirements, or limited access to labeled training data, such as emerging technologies, early-stage product development, or exploratory research. Its low development overhead and fast iteration cycles enable organizations to deploy functional classifiers within hours, adapting swiftly to shifting priorities and new data patterns. However, PT lacks the deep domain understanding required for complex problem-solving and incurs higher inference costs over time, especially when reliant on premium cloud-hosted LLMs. While PT is well-suited for prototyping and low-stakes deployments, it fails to deliver enterprise-level precision and scalability.

The Advantages of Fine-Tuning for Text Classification

As LLMs become increasingly embedded in enterprise workflows, the question of how best to adapt these general-purpose models to specialised, high-stakes tasks has moved from theoretical debate to operational necessity. Our empirical investigation into Prompt Engineering (PE) and Fine-Tuning (FT) provides data-driven clarity on this strategic choice, revealing that FT consistently outperforms PE on supervised text classification tasks in terms of accuracy, cost efficiency, and scalability, even when deployed on local models with under 10B parameters. However, FT is only viable for organisations with access to high-quality labeled datasets and ML-ready infrastructure, such as NVIDIA’s A10G GPUs.

While PE offers rapid deployment and minimal upfront investment, its reliance on verbose prompts and few-shot examples leads to higher token usage and generation costs during inference, especially when deployed on commercial LLM providers. Ultimately, PE achieves lower accuracy than FT, suggesting that LLMs’ general knowledge is insufficient for solving complex real-world problems riddled with tacit requirements, missing information, and imbalanced class distributions. These limitations make PE best suited for environments where labeled data is scarce and task definitions are fluid, such as start-up businesses, emerging technologies and early-stage product development.

In contrast, FT excels in domains that are safety-critical, regulated, data-rich, and performance-sensitive, such as medicine, engineering, construction, and compliance. These fields demand consistent, structured outputs and low error tolerance, making FT’s upfront training investment worthwhile. The long-term gains in cost efficiency, deployment flexibility (including local hardware compatibility), and task-specific accuracy position FT as the preferred strategy for enterprise-scale, high-stakes applications.

Ultimately, FT is the foundation for cost-effective, high-precision adaptation of general-purpose models for domain-specific text classification tasks. In fields like medicine, compliance, and engineering, where accuracy, consistency, and domain fidelity are non-negotiable, FT enables organizations to encode task-specific knowledge directly into the model’s behavior. As access to labeled data improves and open-source tooling matures, FT is poised to become the dominant strategy for LLM text classification. In sum, FT allows for the construction of reliable, scalable, and economically sustainable AI systems for real-world text classification tasks which are invariant to messy data, class imbalances, and domain-specific language.

Appendix

Code Examples

- The code used to fine-tune and evaluate the LLM on the serious injury reports dataset is available as a Jupyter Notebook here: notebooks/osha.ipynb

- For a general example of how to perform systematic LLM text classification of large supervised text datasets, see this example: notebooks/example.ipynb

.svg)

%20v4_resize.jpg)